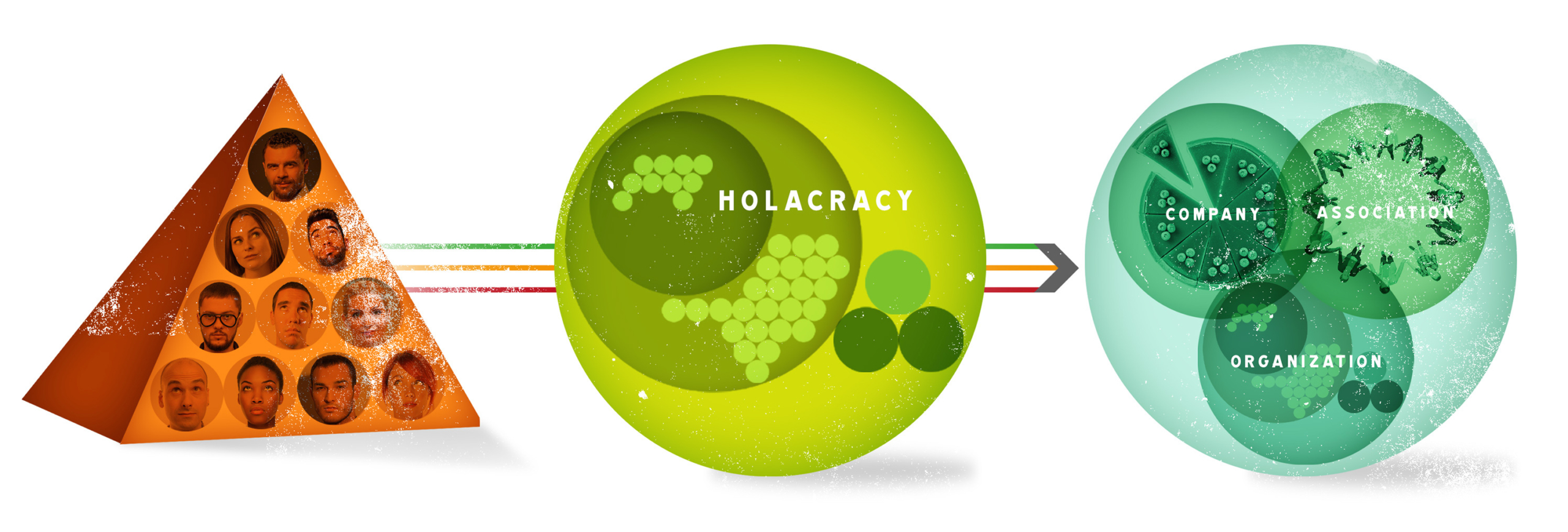

Nieuwsgierig naar nieuwe manieren van organiseren en werken?

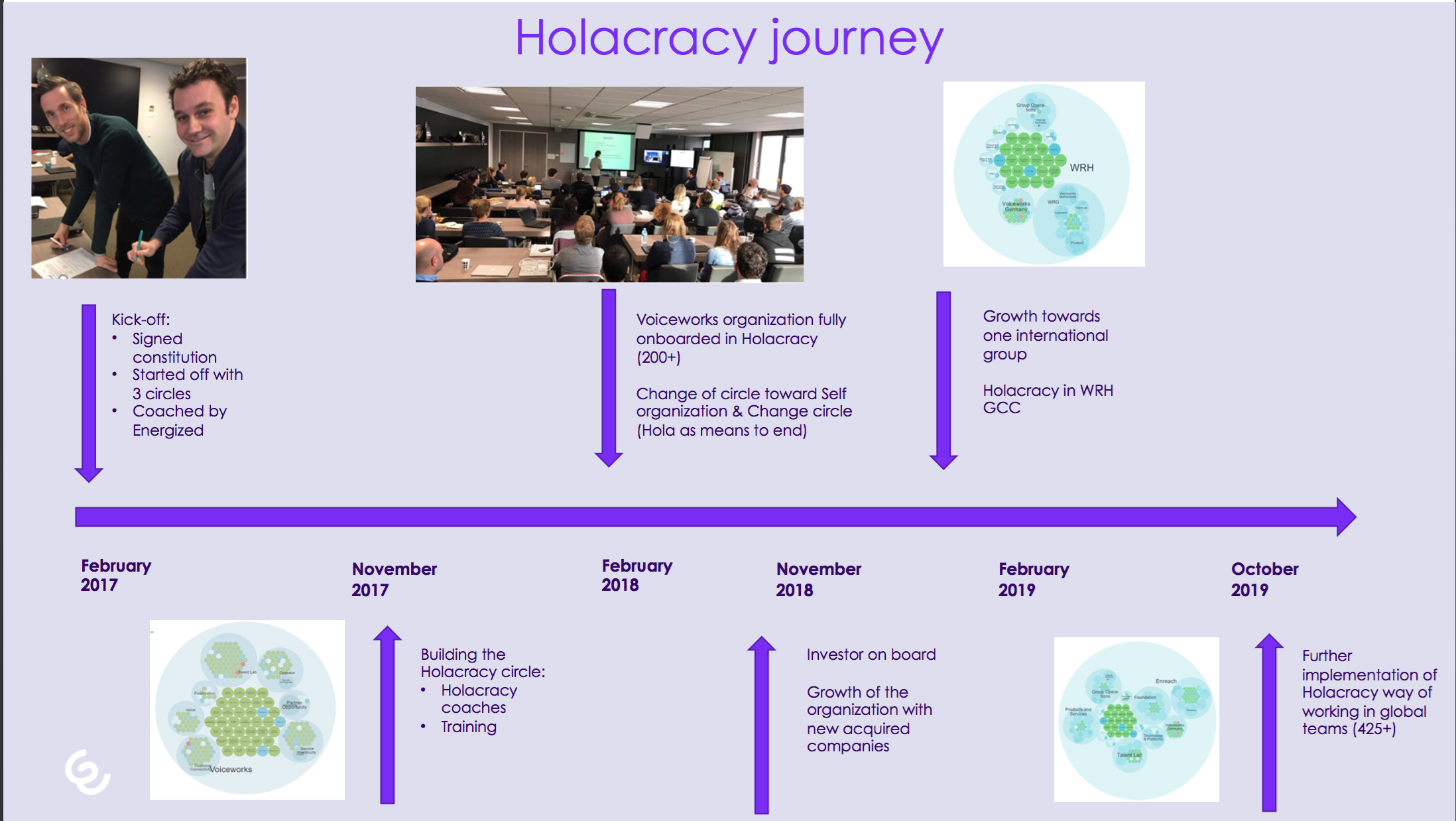

Bij Energized.org vinden purpose gedreven ondernemers inspirerende verhalen van peers en handvatten voor het bouwen van een cultuur van eigenaarschap, zodat ze kunnen groeien in impact.

We supporten je graag met verhalen van andere ondernemers, praktische tips, prikkelende stellingen en reflecties op een nieuwe orde van bestuur.

Welke blogs wil je zien?

Bouwen aan een cultuur van eigenaarschap?

We hebben een hoop blogs, artikelen, handleidingen en zelfs een boek (Getting Teams Done) geschreven. Of je nou de eerste stappen zet op het gebied van Zelforganisatie of je juist wil verdiepen, hier vind je een hoop relevante kennis en informatie.